It's Not A Dead Spruce

Reposted from my October 2022 newsletter, edited for this platform.

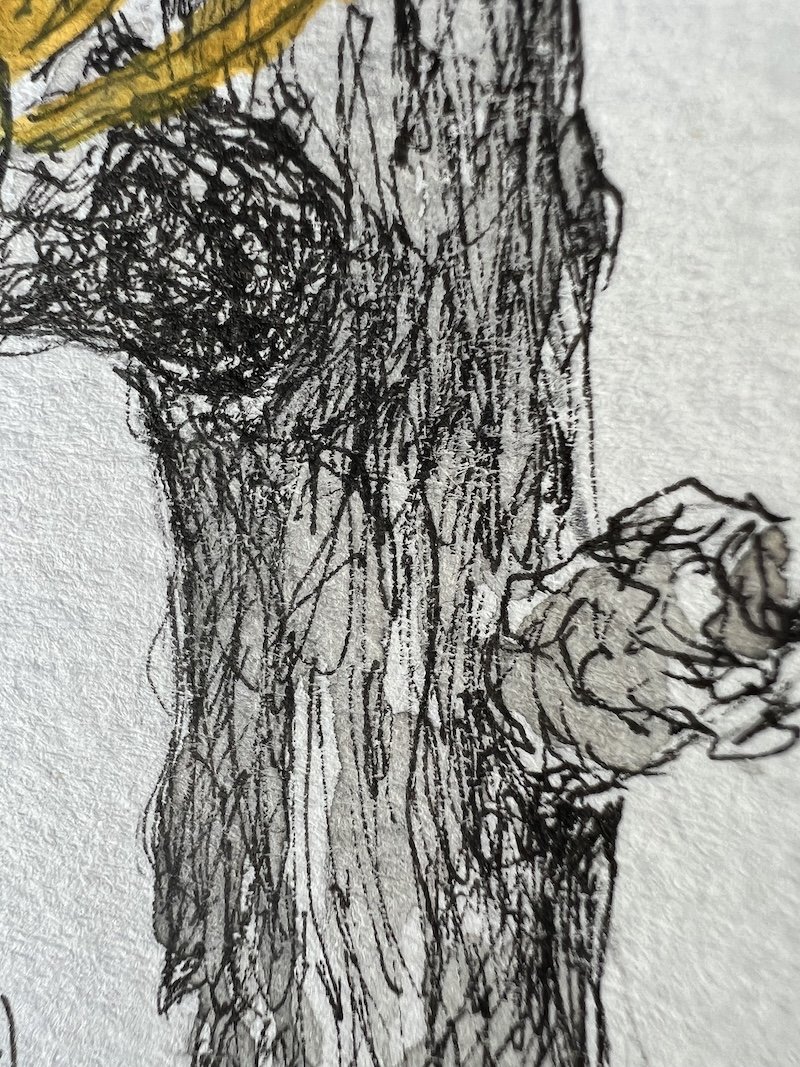

Larix laricina It's not a dead spruce.

Seriously. The Tamarack (Larix laricina), a species of tree that Alaska shares with New England and almost all northern regions in between, is a curious and stunning work of evolution that is often mistaken for its relative, the spruce tree.

Tamarack is in the Larch family, belonging to a small group called deciduous conifers.

That means it has the annual behavior of dropping all of its needles every autumn the same way birch, aspen, willow and other deciduous trees do.

Curiously, it also bears cones as part of the reproductive process as do pines, spruces, cedars, and other species in the evergreen family.

According to the Lake Wilderness Arboretum in WA, there are five genera with about 20 species of deciduous conifers. The genus Larix contains 10 of those species.

The warm golden-yellow of the Tamarack in autumn is so remarkable in intensity, like no other species I know.

It gives a forest of dark, tired greens and grays reason to sing ebulliently one last time before everything goes quiet for the winter.

As part of my explorations of the flora and fauna in Alaska, one of the things I love is stumbling on a species that my "home" home and my "adopted" home share.

A feeling of childlike joy bubbles up... "I know this one!". Both nostalgia and ego play a part in that feeling of happiness.

Just because I can easily recognize the species doesn't mean I know much about it, making this a great opportunity to say, "well, hello there... I'd like to spend some time with you, please."

As I worked on the sketches, my curiosity took over resulting in questions to research.

Why did the deciduous conifer evolve? What's their advantage? Where in the evolutionary line did it diverge and who is the missing link? Which came first, the conifer or the deciduous?

As science often does, finding some answers led to more questions.

To the question of "why", it might come down to the climate and soil that Larches live in: cold, harsh weather conditions combined with typically swampy habitat; the cost vs. benefit of having strong needles year-round.

An added adaptation is having needles that are small (about an inch in length) and widely spaced amongst the branches. Sunlight is shared more evenly throughout the tree, allowing more needles to engage in photosynthesis.

Having twigs that are limber and flexible and needles that drop in preparation for long, cold winters, allows the Tamarack some "give" to move with a heavy snow or ice pack, thus granting it a chance to survive the harsh conditions of Alaska, across Canada, and into northern New England.Interestingly, though, the Tamarack's native habitat extends as far south as the DC area and northeastern PA and northern OH. There's even a few populations scattered in the mountains of WV and MD. Perhaps remnants of the last ice age??

Higher elevations mimic more northern climates, so it seems logical that the Tamarack would find a good home in the mountains further south, beyond the boreal forests of the N. American continent.

Tamaracks in Alaska mostly exist in the interior region and are known as a disjunct group in the subalpine habitat between the Brooks Range to the north and the Alaska Range to the south. That is, they are a distinct population from all the other Larix laricina in North America.

Not all of my questions had answers; it seems there is a lot unknown about deciduous conifers.

Also, there "could" be a morphological difference between the widespread boreal species Tamarack and its western relatives Western Larch and Alpine Larch.

To the untrained eye, you might see how one can mistake this form for a spruce.

It's not uncommon for arborists, dendrologists, local garden shops, or even the US Forest Service to receive phone calls from landowners panicking, thinking their spruce trees are dying.

You might also imagine their relief and wonder when learning it's not a dead spruce at all, but a thriving, magnificent Larch.

Click the image to the right for a 50-second video sharing my experience "getting to know" this brilliant organism. Enjoy!