Bird Migration is About to Begin!

Reposted from my February 2023 newsletter, edited for this platform.

It's true. Birds are on the cusp of initiating their seasonal migration. One question that often comes up is, "How do they know when to go?".

It's not about the amount of daylight or the air temperature, although those might play into the decision.

The angle of the sun is a primary trigger for birds to get moving. One day, when the sun's angle is right, when weather conditions are good and winds are favorable... LIFT OFF!

The specific angle that triggers a bird's annual movement depends on the species. As the sun gets higher in the sky each day, that angle is signaling the approach for departure.

That timing is important. All migratory birds time their flight to coincide with food sources specific to their energy needs, not only on nesting territories but along their migration paths, too.

The longest distance fliers, like the Arctic Tern, will begin first.

They have a lot of terrestrial and oceanic miles to cover to reach their nesting grounds when their preferred food source is available, approximately mid- to late-April.

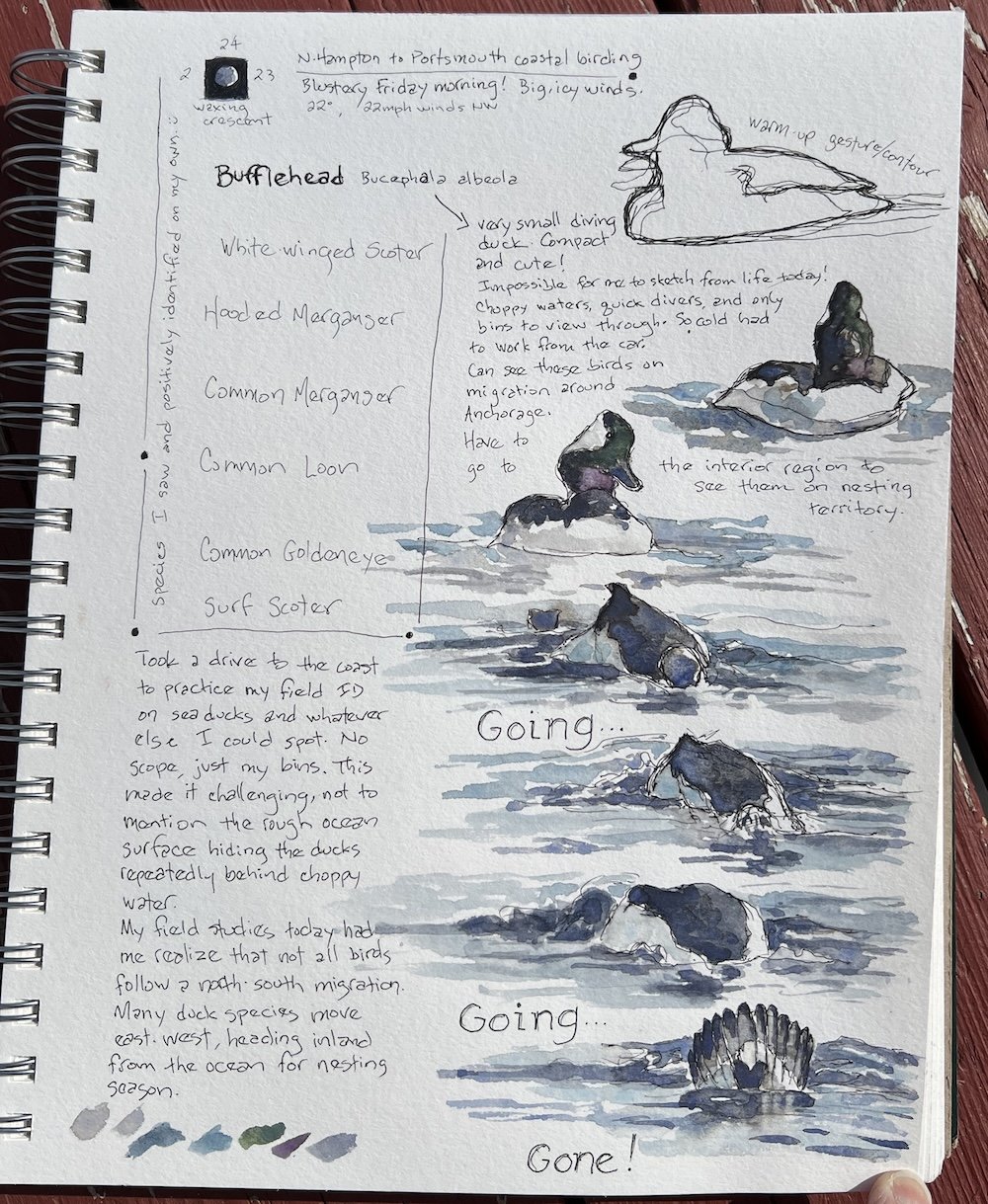

While I was running along the New Hampshire coast recently I looked for ducks and other ocean birds close to shore. Without my binoculars I could see the closest birds and make a reliable guess as to type of bird based on shape.

A few days later I went back to practice my field identification skills with binoculars. I was able to identify seven species close to shore. There were many more dark spots floating and diving further out. Too far to id them without my spotting scope.

Another two days later I went back to the coast intending to use my sketchbook. Sadly, this day was too windy and too cold to work outside.

The wind rolled and roiled the water's surface so that the ducks were bouncing up and down, hidden over and again within the trough of choppy waves.

Plus, the icy temperatures are no friend to field sketching. I was stuck birding from the car while my sketching kit remained in my backpack.

Being there, looking toward the open ocean, got me wondering about sea duck migrations.

Many duck species spend winters on salt bays and open ocean off the Atlantic and Pacific coasts and nest inland during spring and summer. Buffleheads (Bucephala albeola) and Loons (Gavia sp.) are a good example.

It struck with a certain clarity that ducks can have a different migratory path than conventional thought; an east-west direction rather than a north-south direction!

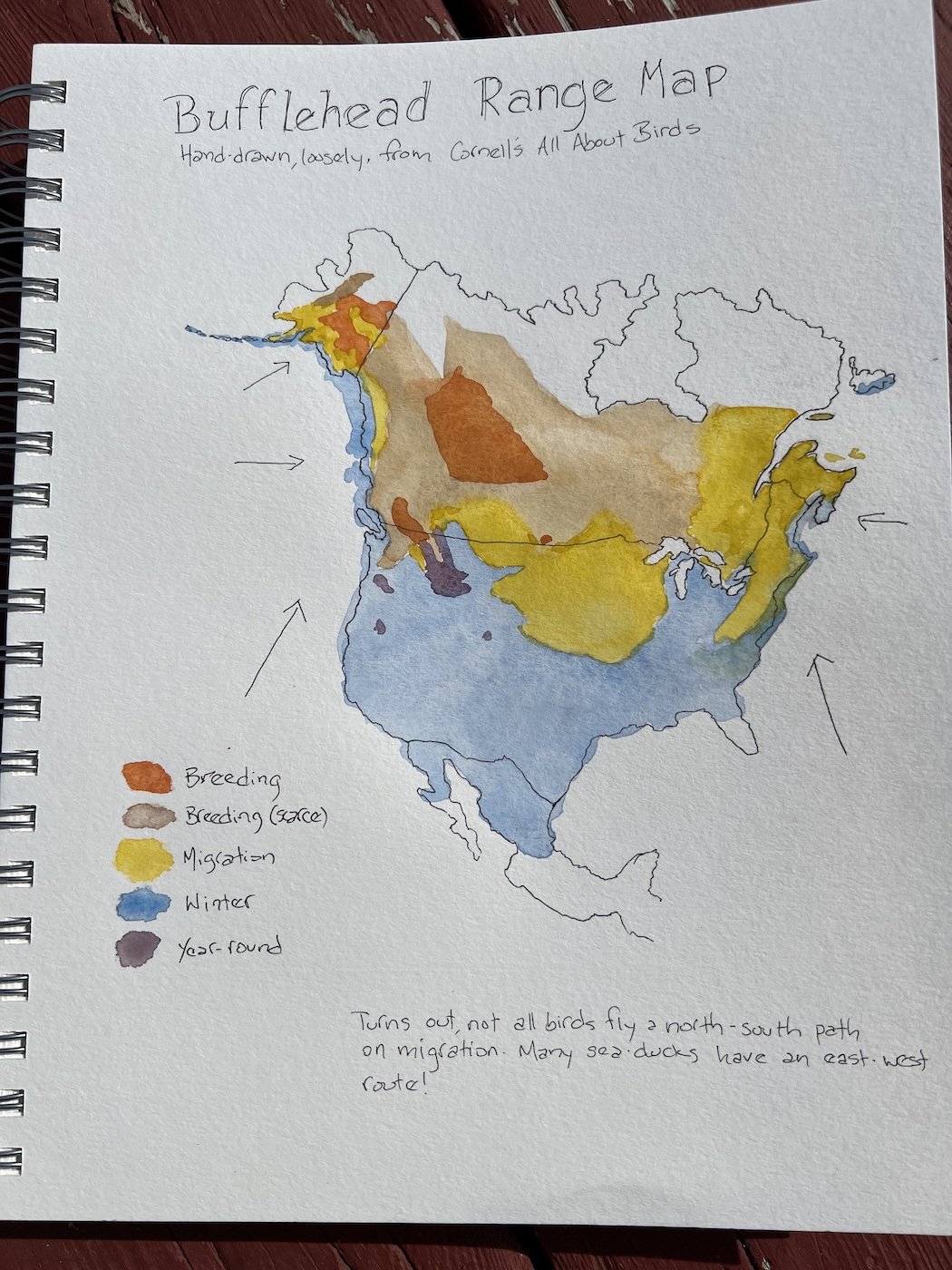

With sudden excitement I decided I need to look into this a bit more. The map here shows the range of the Bufflehead, a compact and adorable diving duck.

You can see that the population which winters throughout the interior U.S. does have a generally north-south migration path but, as the arrows show, it's not that simple.

Populations on the Atlantic coast move northwest and west to reach their breeding grounds, some even head southwest. Those on the Pacific coast move north and northeastward to reach breeding grounds up in the Arctic tundra of Alaska and east into Canada.

For the other six species on my list that day I referenced the Cornell Lab of Ornithology's range maps:

Common Goldeneye (B. clangula range map);

Common & Hooded Mergansers (Mergus merganser range map & Lophodytes cucullatus range map, respectively); and

White-winged Scoter (Melanitta deglandi range map), Surf Scoter (M. perspicillata range map), and Common Loon (G. immer range map)

Summing it up, there are populations of these species that head north to ponds, lakes and rivers in far northern U.S. and much of Canada for nesting. In all cases, however, the farther north one winters, the more likely path to migration will be east-west.

I think that's cool.

My eyes have seen all of these species in both Alaska and in New England, and they're all beautiful birds with interesting behaviors and life histories.

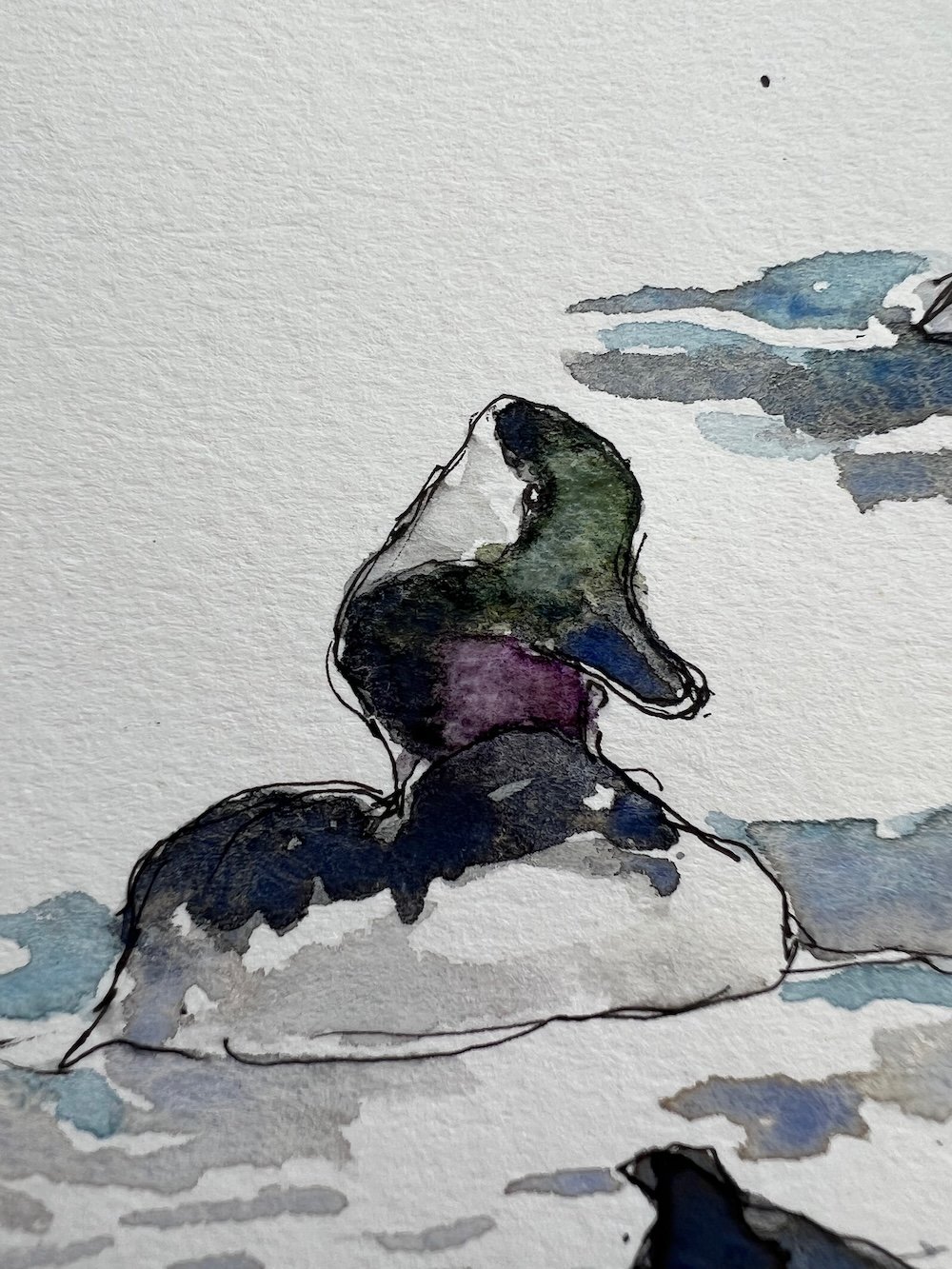

The Bufflehead seemed particularly gratifying that day.

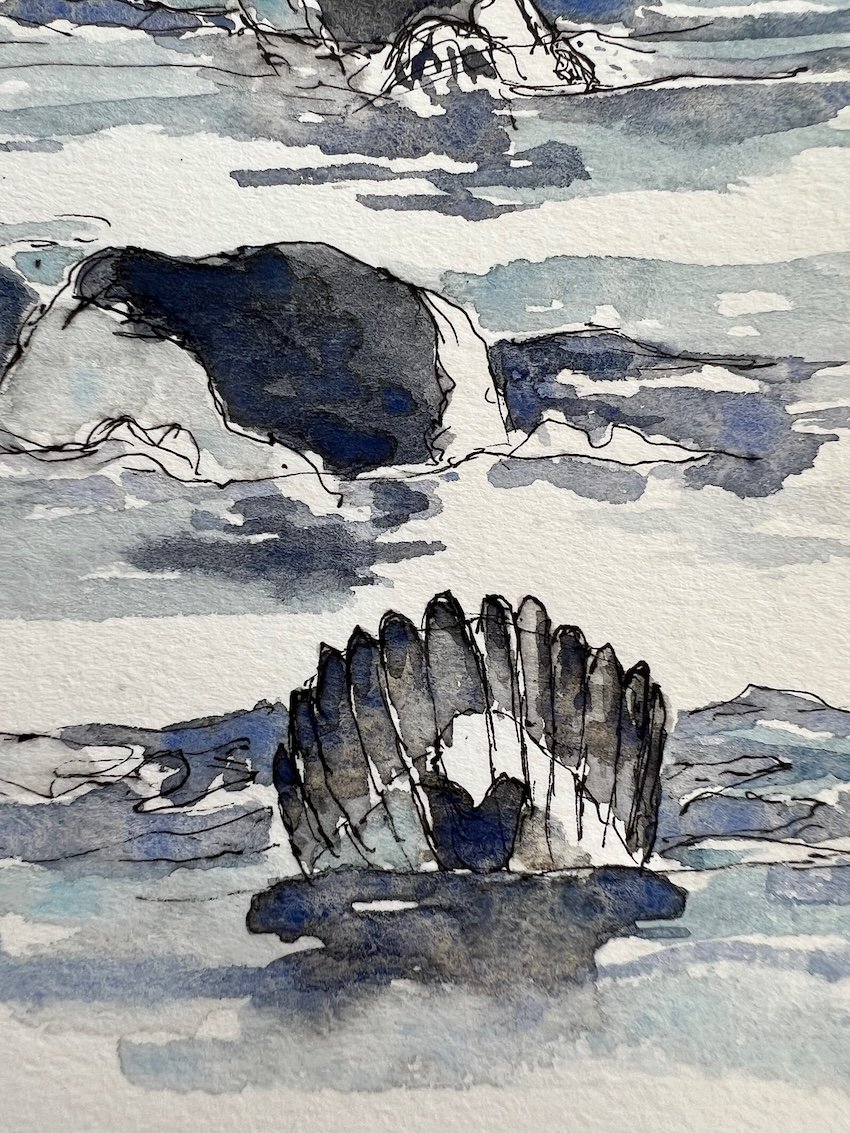

Have you ever watched a Bufflehead's diving behavior? They bob on the surface for a few minutes then, with a forward-thrusting leap, they plunge downward with impressive force. Often whole groups will dive together, one right after another.

Wait a few seconds... a little longer... a few moments more... and you'll see it finally pop up above the water like a cork!

Go check out this adorable, fun bird! They're be bobbing and popping near you until the sun's angle triggers them to move in the direction their genetics and other factors dictate, arriving on territory mid-April into May.